Is Cursive Dead?

Ask anyone over the age of 35, and they’ll probably tell you that a good chunk of their elementary school curriculum was focused on learning the art of cursive. But the skill has slowly fallen by the wayside.

By the end of 2011, 41 states had nixed cursive from their Common Core Standards for English, arguing that the longhand style was time-consuming to teach and less useful than typing, among myriad additional complaints.

Cursive preservationists generally come up short when defending the skill, and as a result, it’s undeniably in the process of going the way of the typewriter.

The important takeaway, though, is that writing the old-fashioned way with a pen and paper isn’t dead, but scribing in script may soon expire for good.

The Argument Against Cursive

The No. 1 reason for why cursive is being allowed to die a slow, painful death is that it’s simply not something people use in their day-to-day lives. A very small number of adults write in cursive on a daily basis, while 78 percent of Americans own a personal computer or laptop, according to the 2015 U.S. Census.

That’s not to say that longhand in and of itself is dead — you’d probably see numbers close to 100 percent if you polled the number of people who owned some kind of writing instrument. It just means that fewer people write in “traditional” longhand than they once did.

Beyond that, cursive contrarians argue that teaching kids print, cursive and typing is too time-consuming (and therefore costly) to justify, especially when almost no one writes in cursive anyway.

In theory, the extra time could be allotted to more practical and applied language arts endeavors, like learning how to use word processors and other technology designed for writing and reading.

The case against cursive also focuses on research suggesting that there is no cognitive or perceived benefit to writing in cursive versus print, no matter how good or bad a person’s penmanship may be.

The Other Side: Benefits of Cursive

By and large, pro-cursive arguments fall into two categories. The first includes arguments that aren’t exclusive to cursive but apply to longhand writing in general, which is still taught under most states’ common core curriculums.

The second category includes arguments of pure preservation — we had to do it, and therefore kids today should have to do it, too. The latter is, naturally, the least compelling argument out there and generally isn’t respected in the cursive debate world, if there is such a thing.

Some legitimate arguments for keeping cursive in the curriculum of schoolchildren include the fact that writing longhand, whether in print or cursive, may actually help kids learn better than typing on a computer. There aren’t any studies indicating that cursive has any greater cognitive effects on learning than writing in print, however.

Others argue that learning cursive helps kids forge their own signatures, which are still needed when signing documents, at least for the time being.

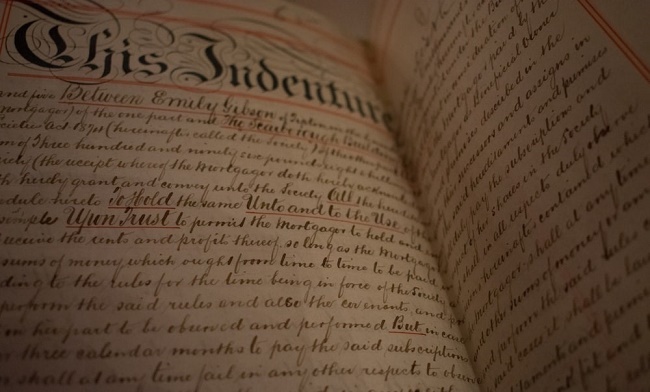

The pro-cursive faction stresses the importance of learning cursive in order to be able to read cursive, since many important historical documents, including the Declaration of Independence, are penned in cursive. It also argues that cursive provides a faster and simpler approach to note-taking.

So far, the arguments from preservationists haven’t been powerful enough to keep it in the core curriculum for the majority of districts in the U.S., but that doesn’t necessarily mean the art is totally dead.

Cursive Is Making a Comeback

So, with all this in mind, the question remains: Is cursive dead? The answer isn’t as straightforward as it might seem. In fact, 23 states have alreapassed legislation to make cursive writing instruction a requirement. California and New Hampshire joined the list in 2023 and Kentucky and Iowa in 2024 became the most recent states to require cursive.

That’s not to say that the adoption has come without pushback — the anti-cursive sector was and continues to be vocal about eliminating the art from curriculum. So just as the art itself requires swooshing and swirling, so too does the push to kill it and keep it alive.

We’ll probably see the skill added and removed from school curriculums a dozen more times in the coming years before anything is officially decided.

Cursive isn’t just coming back into fashion in schools. Because longhand for art’s sake — including calligraphy and hand-lettering — is re-entering the scene as a popular, niche artform, some people are taking more of an interest in learning cursive.

The revitalization of all things penmanship and calligraphy has helped preserve the artform for crafters and hobbyists, but it’s not necessarily an indicator of its staying power in education.

Perhaps the longhand style will join music, art, and poetry in the elective category, or perhaps teachers will opt to teach it during classroom downtime.

Moving Towards the Future

When we look back on history, we rarely lament the loss of one-time cultural mainstays, largely because better options emerged and swept them away for good. What tends to happen is that small groups of hobbyists, historians and collectors preserve the art in a historical context.

Think about the resurgence and preservation associated with vinyl records, typewriters and fountain pens — we don’t need these tools anymore, but it’s important that we collect them, showcase them and use them so that we can understand technology and human development in a broader way.

This is the way that cursive should and probably will evolve. It’s not likely that the art will survive much longer in the few school systems that still require it, so cursive defenders will find new ways to honor the art and help maintain its importance in the larger context of history, education and writing.

Cursive will never actually go extinct because there are too many people who care about preserving it; it will probably simply develop into an antiquated art, preserved and showcased by historians of the future.