Can Employers Require Workers to Take the COVID-19 Vaccine?

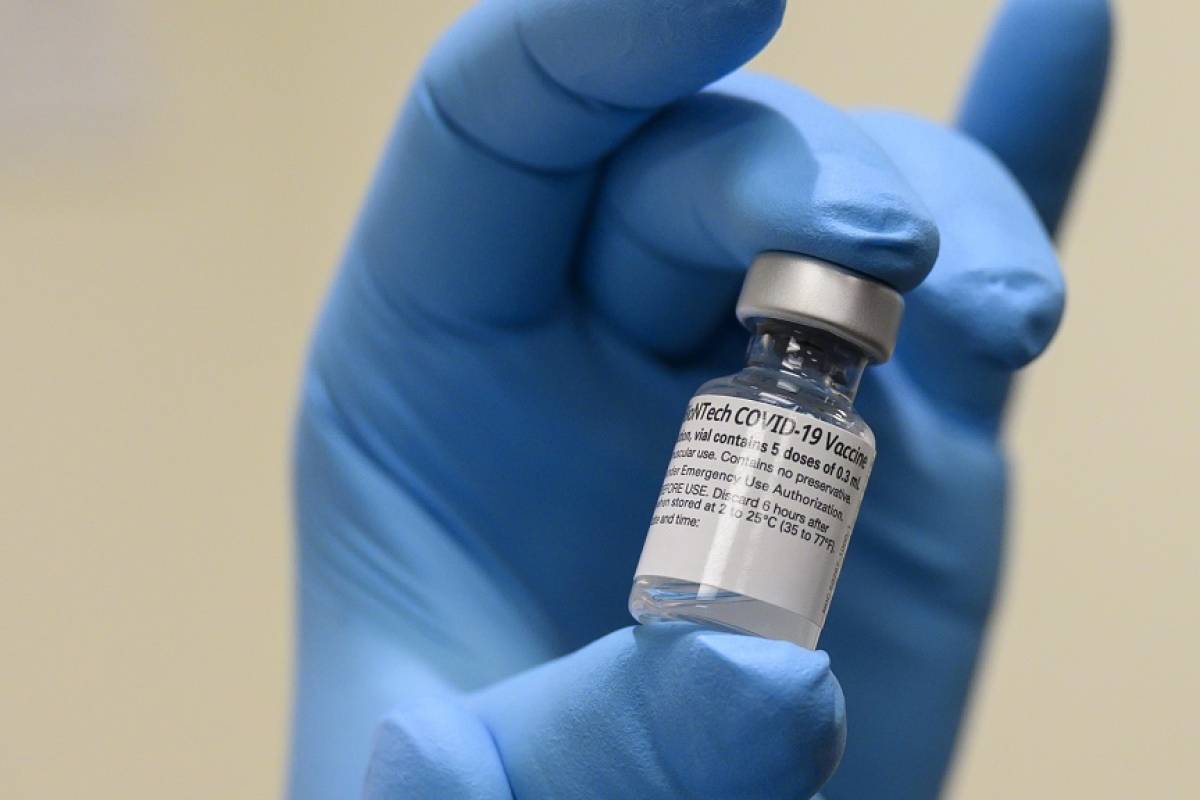

Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 (2020) vaccine. Photo: U.S. Secretary of Defense/Flickr.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the federal agency in charge of enforcing laws prohibiting discrimination in the workplace, on Dec. 16 said that employers can require employees to get vaccinated before entering the workplace.

Now that two COVID-19 vaccines have received emergency use authorization in the U.S., some people are concerned they could be fired if they don’t want to take the vaccine.

We asked legal scholar Ana Santos Rutschman, who teaches a course on vaccine law at Saint Louis University, to explain the decision and the rights employees and employers have.

1. Can employers require employees to get a vaccine?

The general rule is yes – with some exceptions.

Under U.S. law, private employers have the ability to define general working conditions, including the adoption of health and safety within the workspace. Requiring employees to get vaccinated against diseases that could compromise health and safety in the workplace is viewed as part of that ability.

2. Does the rule apply to COVID-19 vaccines?

Earlier in the pandemic, there were some doubts about whether the general rule would apply to COVID-19 vaccines because the first vaccines that became available in the U.S. have not been fully approved by the Food and Drug Administration. They have received an emergency use authorization, which is temporary permission to commercialize the vaccines because of the public health crisis the U.S. is facing. This is the first time emergency use authorization has been granted to a new vaccine. For this reason, some legal scholars questioned whether existing laws applied to temporarily authorized vaccines.

That question was addressed when the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission issued guidelines that said employers have the right to impose a mandatory COVID-19 vaccination policy.

From a legal perspective, this view is based on the fact that the law allows employers to impose requirements to make sure that employees don’t pose threats to the “health or safety of other individuals in the workplace.” The EEOC treated emergency use vaccines as part of the sets of measures that employers are able to mandate in order to accomplish this goal.

Therefore, the general rule applies and employers should be able to require that employees get vaccinated against COVID-19, within certain limits. These limits – including the exceptions below – are the same as the general exemptions applicable to any employer-mandated vaccination.

3. Are there religious exemptions?

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act established that if an employee has a sincerely held religious belief incompatible with vaccination, the employer cannot require that employee to be vaccinated. The EEOC has traditionally interpreted the concept of “religious belief” very broadly. Vaccine refusal cannot, however, be a personal or politically motivated belief.

If an employee qualifies for a religious exemption, the employer must then try to reasonably accommodate the employee. An example of an accommodation would be for the employer to have the employee switch from in-person to remote work while COVID-19 poses risks to public health.

However, the employer does not have to grant an accommodation if doing so would result in “undue hardship.” Typical cases of undue hardship include situations in which the accommodation would compromise the health and safety of other employees or in which implementing the accommodation is too costly or logistically burdensome. In case of a dispute over what constitutes an undue hardship for the employer, a court would typically be asked to resolve it based on the cost of offering the accommodation, as well as how difficult it is for the employer to implement it.

4. How about disability-related exemptions?

The balance of rights between an employee with a disability and her employer is similar to the one described above. Under the Americans with Disabilities Act, if an employee has a disability and cannot safely receive a vaccine, that employee qualifies for an exemption and the employer has to provide reasonable accommodations. But the act also establishes that employers do not have to provide an accommodation that would result in undue hardship.

The technical question here was whether employers could impose COVID-19 vaccination because the Americans with Disabilities Act severely limits the ability of employers to require medical examinations. In its Dec. 16 guidance, the EEOC clearly stated that COVID-19 vaccines do not fall in the “medical examination” category.

Therefore, requiring employee vaccination does not violate federal disability law.

5. What if the employer cannot provide an accommodation?

If an employee qualifies for either a religious or disability-related exemption but the employer is unable to provide an accommodation because of undue hardship, then the employer has the right to exclude the employee from going to the workplace.

Given the broad set of rights that the law gives employers in order to promote health and safety, in some cases it is possible for an organization to go even further and terminate employment if a worker refuses vaccination and there is no reasonable way to provide an accommodation. For example, if there is no reasonable accommodation that an employer can provide a barista that would allow her to continue make lattes at the coffee shop where she works, the employer may be able to terminate her employment.

However, the EEOC guidelines explicitly say that the inability to reasonably accommodate an employee does not automatically give the employer the right to fire her. Finding out whether the coffee shop could indeed terminate its unvaccinated barista would depend on a variety of factors, including state law, union agreements and any other potentially applicable requirements at the federal level.

*This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.