How Award-Winning Creatives Produce Nobel-Prize Type of Work

Belarusian investigative journalist and non-fiction prose writer Svetlana Alexievich was the recipient of the 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature.

If your occupation requires creativity to succeed (such as an occupation as a writer, entrepreneur or other professional), you have probably at some point thought about how you can produce more great ideas and what impact your workplace environment has on your productivity.

Well, in a bid to foster a workplace environment that is conducive to productivity and creativity, today’s cash-flush companies (especially in tech circles) are filling offices with playful indulgences like yoga studios, ping pong tables and even helicopter meeting rooms.

But, are these tactics really working? Do they actually enhance worker productivity and creativity?

Dr. Richard W. Hamming, renowned mathematician and computer scientist who performed groundbreaking research in the computer science arena alongside scientists like Feynman, Fermi and Bethe would have probably said: “These methods might enhance the playfulness of the workplace, but this is just silly” — (probably).

What most people think are the best working conditions, are not.

In a stimulating lecture titled “You and Your Research” delivered in 1986, Hamming sought to answer the questions: “How do award-winning creatives come up with such great ideas; and, why do so few scientists make significant contributions and so many are forgotten in the long run?''

Drawing on more than 40 years of professional experience (having worked with many Nobel Prize winners), and his extensive reading of scientific biographies, Hamming outlined the factors that separate great scientists from mere average ones. He summed up his findings in a spectacular 44-minute lecture.

Beyond the usual aphorisms like start young, follow your passion or work hard, Hamming pulls back the curtains on the ‘Nobel Prize Idea factory’ at Nokia Bell Labs (formerly AT&T Bell Laboratories), and explains how scientific progress was actually made.

It’s a glorious talk, and its lessons extend far beyond careers in science. Among the interesting observations that Hamming makes is about our productivity and when we work best: “…people are often most productive when working conditions are bad,” he says.

Ideal working conditions are not always best

From its beginnings in the 1920s until its demise in the 1980s, Bell Labs (the research and development wing of AT&T) was the biggest and arguably the best laboratory for new ideas in the world, says Jon Gertner in his insightful book “The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation.”

Researchers at Bell Labs were inventing the future in all kinds of ways, doing pioneering work on solar cells, lasers and communication satellites. A couple of scientists even discovered the first echoes of the big bang by accident. And yet these researchers initially worked from less than ideal conditions.

“This brings up the subject, out of order perhaps, of working conditions,” says Hamming “What most people think are the best working conditions, are not. Very clearly they are not because people are often most productive when working conditions are bad.”

And Hamming tells a personal story why he came to this conclusion:

“I give you a story from my own private life. Early on it became evident to me that Bell Laboratories was not going to give me the conventional acre of programming people to program computing machines in absolute binary. It was clear they weren't going to. But that was the way everybody did it. I could go to the West Coast and get a job with the airplane companies without any trouble, but the exciting people were at Bell Labs and the fellows out there in the airplane companies were not. I thought for a long while about, ‘Did I want to go or not?’ and I wondered how I could get the best of two possible worlds. I finally said to myself, ‘Hamming, you think the machines can do practically everything. Why can't you make them write programs?’ What appeared at first to me as a defect forced me into automatic programming very early. What appears to be a fault, often, by a change of viewpoint, turns out to be one of the greatest assets you can have. But you are not likely to think that when you first look the thing and say, ‘Gee, I'm never going to get enough programmers, so how can I ever do any great programming?’''

You see, despite being light on amenities, Bell Labs researchers executed some of the best scientific work ever produced in the United States. And there are so many other stories of the same kind.

“I think that if you look carefully you will see that often the great scientists, by turning the problem around a bit, changed a defect to an asset. For example, many scientists when they found they couldn't do a problem finally began to study why not. They then turned it around the other way and said, ‘But of course, this is what it is’ and got an important result. So, ideal working conditions are very strange. The ones you want aren't always the best ones for you.”

Deficit, discomfort is not always bad

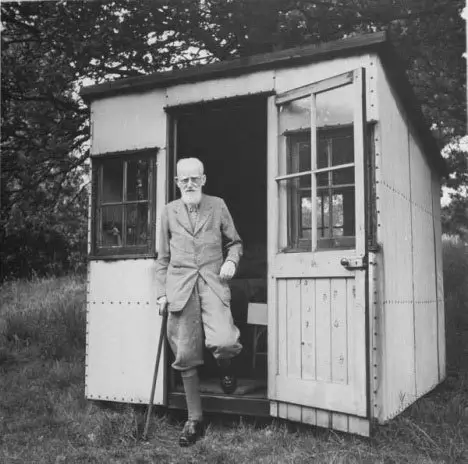

George Bernard Shaw’s writing shack dubbed “London.”

Shortfall or deficit and discomfort are rarely sexy, but as biography after biography will attest, you can still produce world-class work in absolute squalor. Despite living in Hertfordshire, George Bernard Shaw, for example, called his writing shack “London.” That way, his secretary could honestly say that Shaw had “gone to London” when he retreated to the backyard to write his Nobel Prize-winning plays.

Similarly, Svetlana Alexievich, winner of the 2015 Nobel Prize in literature, has worked in less than ideal conditions for more than 30 years. She has explored conflict and its aftermath all over the former Soviet Union, shedding light into the emotional lives of people she has met from Chernobyl to Kabul.

Though persecuted greatly, particularly by Alexander Lukashenko’s dictatorial regime in Belarus, Alexievich kept going—giving voice to survivors of conflict and disasters. According to the Nobel Prize judges, she was given the award “for her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time.”

People who do first-class, award-winning type of work think through – in a careful and deeply researched way – a number of important problems in their field or environment. They commit to the issues, become emotionally involved and look for ways to address the problems. And they actually attack the major problems squarely, marching forward day after day after day in the direction they believe is important despite any uncomfortable conditions.

On the other hand, people who make mediocre contributions in this world often want to work in ideal conditions and operate from an architectural paradise without realizing you can still end up producing derivative drivel even under “perfect” or cushy working conditions. As Hamming mentions, “It is a poor workman who blames his tools – the good man gets on with the job, given what he's got, and gets the best answer he can.''

Joe MacNeil, writer at Crew Blog, calls to mind Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) – a luxurious, all-expenses-paid resort for Nobel Prize winners like Albert Einstein. The institute was responsible for less groundbreaking scientific papers than any dingy Swiss patent office ever was.

While Einstein’s move from Berlin to Princeton had been hailed as bringing “the pope of physics … to the United States, (which) will now become the center of the natural sciences,” Einstein—even with all his talents—failed to publish a single significant paper during his twenty-year tenure at the IAS.

His cozy New Jersey corner-office was to no avail, says MacNeill.

Get out of your comfort zone and attack the major problems headon

If you want to make significant contributions in life, there is no denying the value of getting out of your comfort zone and making the most of what you already have no matter how small. This attitude helped elevate the careers of Bell Lab scientists, as well as award-winning writers as far-ranging as George Bernard Shaw, Henry David Thoreau, Mark Twain and Virginia Woolf.

However, what made the Bell Labs particularly special wasn’t the lightness on amenities itself, but the fact that over lunch you could trade ideas with some of the best creative minds in America. When you study the lives of the most successful people, you’ll notice a recurring pattern: they always worked with great people, often in less than ideal conditions.

By the late 1940s, there were about 9,000 people working at Bell Labs, Gertner tells NPR. And by the height of its reputation, around the late '60s, there were about 15,000. And then before the phone company was broken up, there were about 25,000 people – plenty of brilliant people to work with.

The award-winning exploits done at Bell Labs themselves might have been produced in solitude, but they were always inspired by conversations with peers over lunch, dinner or drinks. This is how you generate new ideas and make significant contributions: You draw from others and do your job in such a way that others can build on top of it, so they will indeed say, “Yes, I've stood on so and so's shoulders and I saw further.''

Congregate, debate, trade ideas with others

Consider the poets who gathered at Pfaf’s beer cellar, writes MacNeil; comics who congregated at the Algonquin Round Table; rappers who met at Magic City; impressionist painters who lived together at Giverny; they spent a great deal of time socializing with one another. Even ‘reclusive’ artists socialized with others, including Hemingway, Fitzgerald and Picasso who exchanged barbs at the Stein Salon.

When you congregate and debate with others, great ideas will collide. And the results are often spectacular. You will improve your ability to come up with more powerful ideas and ultimately produce award-winning type of work. So, get out there more regularly. Interact, relate, debate, exchange ideas with other people even if you don’t have the same exact common ground. Keep active in places where something might happen. It will give you clues as to what the world is, what it wants and what is actually important.

“The more you know, the more you learn; the more you learn, the more you can do; the more you can do, the more the opportunity—it is very much like compound interest,” says Hamming “I don't want to give you a rate, but it is a very high rate.”

See Also: How to Attract Great Opportunities into Your Life.